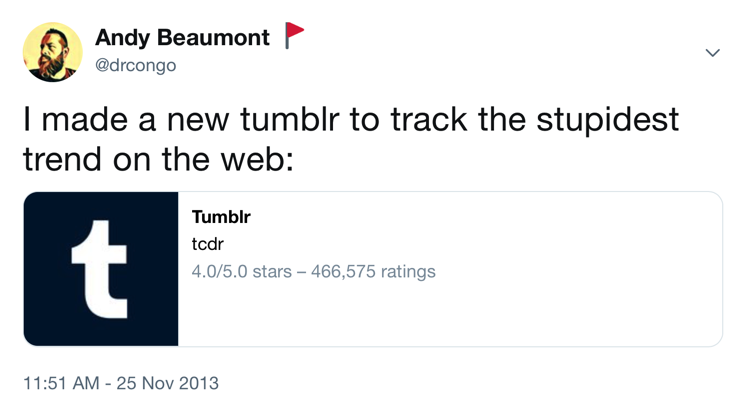

TC;DR

I made a Tumblr that accidentally went viral. For a year or so I’d been collecting screengrabs of websites that obscure their content behind modal overlays, begging for newsletter signups, follows, likes, or even adverts that direct you to another site entirely. In the words of Brad Frost, bullshit. Throughout that year they were becoming more and more prevalent and more and more invasive. I made a Tumblr site to collect them on, called it Tab Closed; Didn’t Read and posted one lone tweet announcing it to the world.

I quickly discovered I was not alone. Thousands of people tweeted the URL, it made the front pages of Hacker News and Reddit, and submissions started pouring in.

What we’re witnessing here is the first wave of the second world pop-up war. Those of us who lived through the first one can only describe the horrors to our disbelieving children. This time though, the pop-ups are winning because we don’t yet have the tools to fight back. The web has seemingly evolved into something that actively antagonises people — why would anyone in their right mind hide the content that visitors are there to see?

In short, maybe they’re not in their right mind. This is what happens when analytics make decisions for you. In amongst the thousands of tweets about TC;DR there were a few dissenting voices.

Note the 100% figure — absolute certainty. This kind of belief in numbers is exactly what got us into this mess. Analytics only tell you part of the story — if that’s all you bother to find out, and you have absolute faith in those numbers, then you’re going to end up putting a modal overlay on your site. Analytics will tell you that you got more “conversions”. Analytics will show you rising graphs and bigger numbers. You will show these to your boss or your client. They will falsely conclude that people love these modal overlays.

But they don’t. Nobody likes them. Conversions are not people. If you want the whole story here you should also be sat in a room testing this modal overlay with real people. Ask them questions:

- “Do you like that overlay asking you to sign up for the newsletter?”

- “Do you understand what will happen if you do sign up for it?”

- “Do you know that there is content behind it?”

- “Do you know how to close it to get to the content?”.

It’s extremely unlikely that they like it. It’s fairly likely that they do know there is content behind it. And it is also fairly likely that they don’t know how to close it.

I have tested this design pattern with real people, and a significant portion of them believe that they must do what the box is begging them for in order to close the overlay. These people (remember, they’re people, not “conversions”), are signing up to a newsletter they don’t want. They’re then going to be irritated by it for several months until they work out how to unsubscribe from it. The analytics guru you brought in is walking away with a chunk of your money, in exchange for having pissed off a whole bunch of existing and potential customers.

Particularly baffling is when this technique is used by content publishers. People are there to read your content — but you’ve hidden it, like you’re ashamed. The message this sends out is that the publisher simply places more value on being liked on Facebook than they do on their own content. This seems like a pretty good indicator to me that I’m not going to value the content on there either.

More generally, the web is dumbing down as the fight for attention hots up. Quality publishing is losing huge amounts of money, while sites like BuzzFeed spring up caring nothing about the content, only about hits, clicks and likes with their $(num) $(noun)s That Will Make You $(verb) headlines and articles that are nothing more than lists of things they’ve seen on Reddit. It’s publish and be damned, for all the wrong reasons. The age of Idiocracy is already here and the Daily Mail is the world’s number one online newspaper.

If you’re a quality publisher it’s hard to fight this. Paywalls are difficult; you need to be a certain kind of reader subscribing to a certain kind of publication. It works for The Financial Times because they’re the only quality newspaper in the UK focused on a specific market of people who have to read it to be able to do their job.

If you’re not lucky enough to be a certain kind of publication, how do you allow people to see enough of your site and your content for them to want to pay for it? Byliner didn’t make it on to TC;DR because they’re making a very good attempt at doing exactly this. I can read almost enough content to be able to judge its value to me, and then I get a very clear explanation of what’s on offer if I subscribe. I really hope it works out for them, but I fear it won’t.

But while half the web succumbs to the disease of intrusive overlays, there are quiet pockets of resistance. Sites like Quartz are rethinking what publishing on the web should look like. They’re not aping the print media of the past, but looking to the future instead. Medium gives so much care and attention to your content that almost anything on there automatically feels of value. The New York Times’ Snow Fall experiment, while not to everyone’s taste, at least shows a real love and respect for the content — so much so that snowfalling has become a verb. Some of the feature articles on Mojo are sublime.

The problem is that good content costs money, and someone has to pay. There are better ways than annoying your visitors though. Matter was a Kickstarter project that asked people to pay in advance for the promise of quality investigative journalism. It smashed its target and published some thought-provoking stuff that wouldn’t have appeared anywhere else (it’s since been acquired by Medium). Marco Arment started The Magazine, a fortnightly iOS periodical, that has “healthy” subscriber numbers (including me) and now has a distribution deal with, of course, Medium.

I believe in paying for good content. I don’t pirate movies or music, and so it figures that I’ll also pay to read quality content. Surely there must be more like me? People who appreciate that somebody, somewhere is putting craft and effort into creating something, and that these people need to get paid if we want that to continue?

If we want quality content on the web we need the kind of disruption that the iTunes Music Store had on music or Netflix on movies; but not in the form of a yet another content platform. I think that the revolution, if it happens, will be in a micro-payments platform. The first person to work out a way that normal people can understand and use Bitcoin will win the internet.

Click here to pay $0.05 to read the rest of this article.

Note: This article was originally posted on Medium, but Medium has a really shitty reading experience these days.